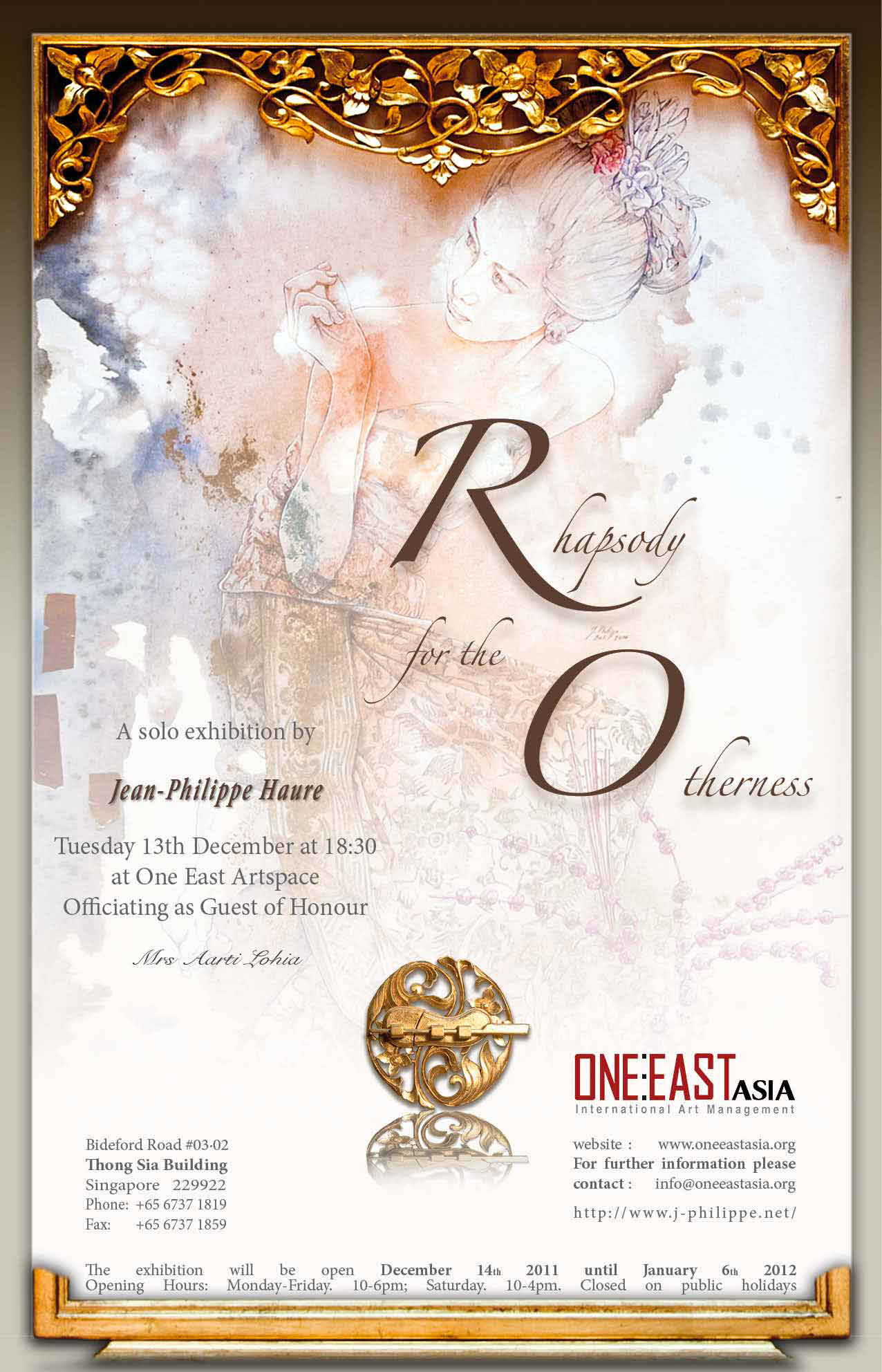

Jean-Philippe Haure’s spiritual sublimation of the real.

THE ART

The eye is first drawn to the soft-hued, reddish or bluish drippings and hazy wash layers spread over the paper surface. Blots appear here, a gravel-like texture there; vague shapes stand out and then melt away. There emanates an impression of calm and peace. It is haphazard “abstraction” at its best: a language of purely visual emotions expressed through a seemingly surreal color world. Yet, as the eye rests longer on the paper, another reading reveals itself, this time figurative: behind the pastel wash colors lurks the vague, yet finely drawn contours of a Balinese dancer or a classical Balinese village scene. Our emotions, awakened by the abstract side of the work, are now guided toward the visual enjoyment of what is a realistic image of Bali, yet, at the same time, an unreal world that is more than simply “Bali.”

Here is an artist who is obviously interested not in formal considerations per se—his combination of abstraction and figuration is only a tool—but by an endeavor, one should almost say an urge, to express what is to him the pristine and the pure. Which he finds best embodied in Bali, and in the Balinese woman. Not because they are icons, but because both are to him the best available manifestation of this ideal, in their natural gestures and feminine simplicity. Had he been born in 15th century Italy, he would probably have painted Madonnas and Tuscan landscapes, the ideals of painting of that time.

Jean-Philippe Haure always begins painting with the “hazy” abstract beige or brown color characterized above, to create an atmosphere that dampens realism to take us somewhere beyond it. This “haze” can be construed to represent the “unknowable” that remains the realm of each of us in our irreducible separateness. It may also bring to mind the dreams of dancers or the suffering of the elderly. At a deeper level, it evokes the “beyond” that links separateness, dreams and pain, and eventually all of us, into the same Unknown that calls us to meditation and prayer.

How does he achieve his idealistic kind of representation? By an original combination, in his technical creative process, of both abstraction and figuration, which he turns for this purpose into a dialogue of line and color, each with a well-defined and separate function. Color defines the mood, and generates the desired “feel.” It does not shape objects or characters, nor does it follow an underlying graphic structure. This mood is achieved very economically, with only two, at most three basic colors (brown and gold, and sometimes blue) applied in an array of hues spread in tachist patches, which defines space and composition in a semi-automatic, semi-intuitive, never pre-organized way. Thus, in Jean-Philippe’s works, it is color that structures the painting, in an abstract way, after the manner popularized by American Abstract Expressionism and French Tachism.

His first thrust of color aims to create a certain visual rhythm. Of course, he does not always succeed. If so, he then discards the piece under way and takes up another one. “If I don’t like the wash surface I have made," says Jean-Philippe, “I just don’t carry on. I don’t draw anything. I leave the work unfinished.” When he has found the basic rhythm, he reworks it over and over, as images suggest themselves to him. These images are all photographs that he has made while attending the pageant of ritual life in Bali. They contribute the lines, and eventually, the ideational content of the work. But how can a photograph do this? By lending only some of its lines, the most evocative ones, while letting go of any overly narrative, detailed content. Of the photograph, there will eventually remain only the minimum needed to suggest a scene, and through this scene, a certain understanding of sensitivity, tenderness and love. Everything is suggested rather than affirmed. As a flowing mood than runs beyond the colors into the lines of the sublimated real.

From the point of view of content, as will be seen at a deeper level later, Jean-Philippe’s paintings are anything but exotic. Exoticism is basically a misunderstanding. It underlines the outward differences of a culture, as if these differences represented its core, whereas they are simply details. With regard to Bali, exoticism hovers around ceremonies, offerings and the like, all that has contributed to the island’s paradise image.

This is not what Jean-Philippe is after. The characters he represents in his works do not surprise us by their otherness, but instead, by the intimacy they emanate. What he sees in them are ordinary bodily gestures and a sense of togetherness. Innocent humans as we all should be. This perception of Bali as a land of innocence is very personal: Jean-Philippe does not impose it upon us, but rather reveals it, little by little, as the background of his color wash. The main quality of the artist here appears, beyond his style and technique: his sensitivity as a man of faith, open to other men and Humanity as a whole.

Jean Couteau